When I was 22, I was operated on to remove a large ovarian cyst. Keyhole surgery and back home that afternoon was the suggestion; instead I nearly died.

The operation did not go as planned and I had to have four blood transfusions to replace my significant loss. I was a week in hospital and it was several months before I felt my strength return on so many levels.

During my recovery at home (if memory serves, just a few days back from hospital), I became upset when my mother left me alone in the shower to answer the phone. I couldn’t lift my right leg more than a few centimetres off the ground and I felt trapped within the high bath sides. My mother returned to find me in floods of tears. She sighed and told me that I was getting a ‘victim complex’.

What I really had was PTSD.

My mother’s family and background is one of army and boarding school, so I fully understand that she had been raised to have that stiff, British, upper lip and empathy was not a trait much nurtured, but wow those few words smacked me hard.

They spun around my head for years and years trying to tally with the way I had felt post that operation (and all the others shifts that had been made because of it – change of job, country and relationship). I believed my mother. I believed I was not handling my trauma ‘well enough’.

What I also noticed over those years was how invested I was in telling the story of my operation. It felt like such an enormous part of who I was; I would drunkenly insist on revealing my physical scars to all those that listened; it became an excuse for all my failings – weight, relationships, jobs. Most telling of all, I could barely recount the full story without feeling like collapsing into unending tears.

It was only when I began to explore the world of healing that I started to empathise with that younger self and the overwhelm I had been dealing with. I realised that without the right tools and support I had been left with two choices, the stiff upper lip of denial or the Groundhog Day story that defined me completely.

But there is a space in between denial and holding on to the story, neither of which serve, and that place is one of healing. That delicate place of acceptance – something happened to me and I was a victim without becoming victim to that trauma. I think that nuance is key to addressing how trauma can be honoured and processed and also crucial to moving beyond the potential to remain fixed in a story that can inhibit growth and vitality.

That space is one of liberation and is the right of everyone and it is a space that needs to be consciously chosen and strived for. It is a doorway that requires effort and application to open. It is not easy nor is it meant to be.

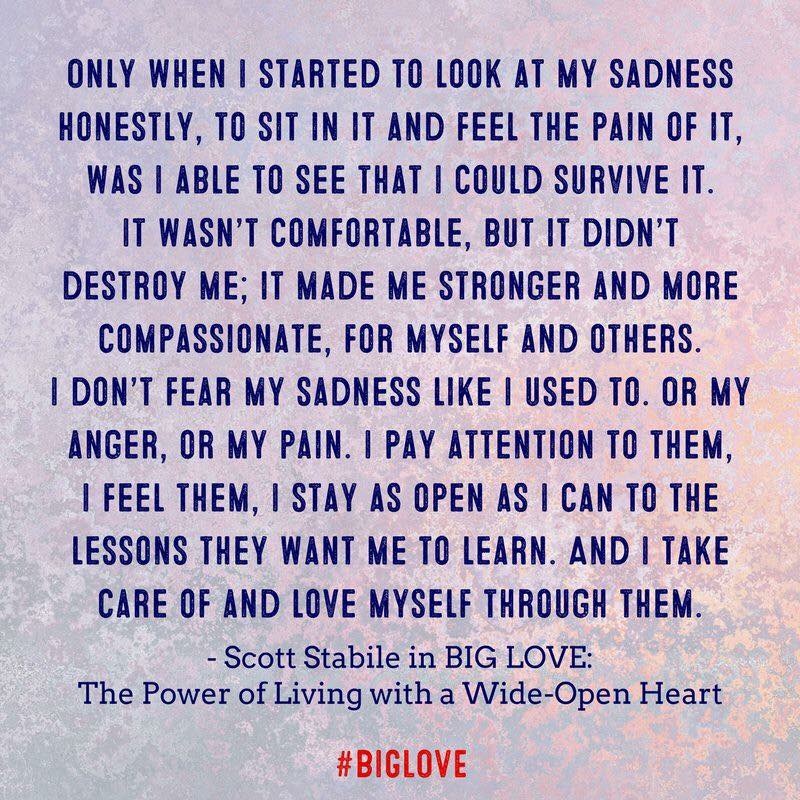

As Scott Stabile’s quote says ‘…I could survive it. It wasn’t comfortable, but it didn’t destroy me.’